Ediciones La Llave published in 2021 ‘El viaje sanador’, the first edition in Spanish of a classic book by Claudio Naranjo: ‘The Healing Journey’, published in English in 1973 and, nevertheless, very topical, now that the taboo on therapeutic research with psychedelics, a field in which Naranjo was a pioneer, is finally beginning to be broken.

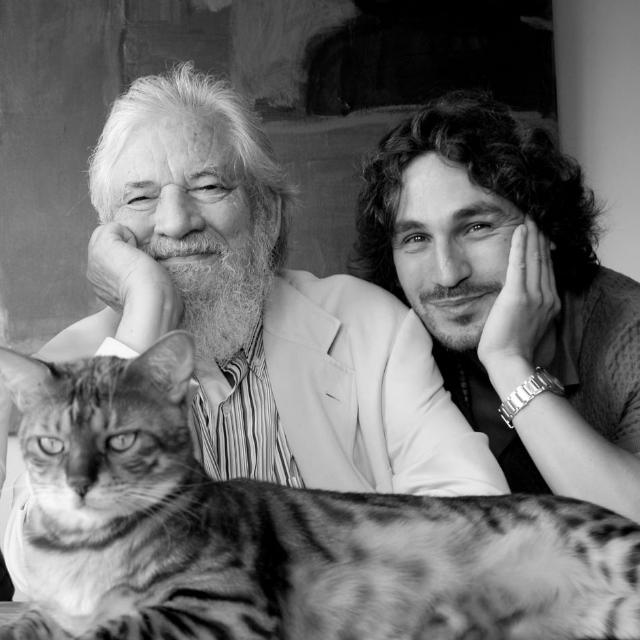

We spoke to David Barba, editor of La Llave, member of Fundación Beckley Med,and an advanced disciple of Claudio. Through his words, David brings us not only snippets of the master’s wisdom but also his own, after decades of deep personal work with Gestalt, Buddhism and, of course, psychedelics, including ayahuasca.

What was your relationship with Claudio Naranjo?

I am a journalist and editor of Ediciones La Llave, an imprint specialising in transpersonal psychology, meditation, Gestalt, psychedelics and Eastern and Western religions. My bond with Claudio Naranjo has been as a student, he has been my mentor, a teacher for me, or rather an anti-teacher, because Claudio Naranjo always had a bamboo stick in his hand with which he gave to his students, especially those closest to him. This bond grew stronger, I became his editor, I spent ten years editing his books and I learned a lot from this man, who was very prominent, both in California in the 60s and in Spain in recent years, where he has played a very important role in spreading the culture of psychedelic and humanist therapy in general.

Claudio’s profound knowledge of psychedelics, especially ayahuasca, is still surprising.

Yes, Claudio was asked by Ricard Evans Schultes, then director of the Harvard Botanical Museum, to go to the Colombian jungle to collect samples of the famous Banisterioosis caapi, the ayahuasca vine, when he was very young, in 1962. Claudio went into the jungle. Although Spruce, Schultes and some German researchers had previously made this journey in search of the vine, Claudio was one of the few white people who went deep into the jungle and got to know the potion first hand. From there he became one of the key researchers, not only in psychopharmacy – we can speak of his ten-year partnership with the chemist Shulgin – but in psychotherapy, where he was a pioneer in discovering the therapeutic properties of various psychedelic substances.

However, for Claudio, ayahuasca was more than just a psychedelic, it had something special, it was an “onirophrenic”.

For Claudio, ayahuasca is the substance that puts people most in touch with the body, with the “organismic”. In Gestalt therapy, where Claudio was a pioneer together with his teacher Fritz Perls and the first world reference in the last decades, the concept of “organismic self-regulation” is very important, i.e. the body knows what the organism needs to be well. In a way, ayahuasca is a very important substance in this sense. The inner animal, which is normally trampled underfoot, acquires its full dimension in an ayahuasca experience. In this vindication of the inner animal, in this eternal struggle between culture and nature in which our techno-scientific Western civilisation is immersed, Claudio sensed that there was a great potential for healing there. For him, ayahuasca was the main plant, as the generator of a fantastic imagery that dissolves the ego from the belly (unlike classic psychedelics, which dissolve it from the head, or empathogens, from the heart) and that “works” with animal impulses.

Can we say that the use of psychedelics is already imprinted in the DNA of Gestalt since Fritz Perls, it is not something of Claudio’s?

I think so, among other things because Gestalt is a great sacred prostitute able to associate itself profitably with any other tool. Fritz Pearls was a great consumer of LSD. The reinvention of Californian Gestalt that Fritz Pearls himself carried out when he saw the excessively psychoanalytical and behavioural drift that his disciples were taking in New York, I believe that this contact with LSD and other substances was of capital importance, above all because it made Gestalt the therapy of the counterculture and the bridge between the therapeutic and the psychedelic made it possible to establish a psycho-spiritual therapeutic culture, a culture where the taking of a psychedelic substance was not a mere recreational resource but a journey into deep consciousness guided by professionals with great expertise in mental health and in the journey of life, including Claudio himself. It is in this cultural revolution of the sixties that Claudio plays a fundamental role, along with Allan Watts and many others.

How did Claudio and Gestalt manage to avoid the ban of the seventies in order to continue with psychedelic therapy?

There are many psychologists, therapists and also shamans who for decades have done what I would call humanitarian work, even at the risk of their own freedom, to care for many suffering people in need of a new paradigm in psychopharmacy and mental health. As we all know, psychiatric pharmacy lags far behind the rest of medicine. Nothing new has been invented in 40 or 50 years, we only have antidepressants, antipsychotics and little else. The war on drugs, which is a political and cultural war, has been the impediment to new, more powerful and more useful tools for mental health. And when we talk about mental health, we are not only talking about individual health, but – I use this term that was very dear to Claudio – about psycho-spiritual health and social health, the health of our culture. You don’t have to be very clever to realise that the health of our culture is pretty decrepit, unless you are Stephen Pinker and you think everything is fine.

In ‘The Healing Journey’, Claudio refers to “harmaline” rather than ayahuasca. What exactly was the substance he used at that time?

Harmaline is one of the active ingredients of ayahuasca, together with harmine and DMT. What Claudius did was to get synthesised harmaline and work with it. In general, DMT has been considered as the main substance and harmine, tetrahydroharmin and harmaline, which are active principles of Banisteriopsis, not Psichotria, have been considered as “second division”. Claudio studied harmaline because he thought this substance had a lot to say, and indeed, you can see in the book that it is a potent substance, leading to visions and feelings of great healing power, and Claudio became an expert also in the use of this substance as well as MDA, the precursor of MDMA, MMDA and ibogaine.

It is curious how in the West we are giving a predominant place to DMT, when in the jungle ayahuasca is what gives the drink its name, so its active ingredients should be more important.

I have had one experience, as far as I know, with harmaline, because sometimes Claudio did not tell you what you were taking, precisely to avoid conditioning you with an expectation of concrete results. On one of the occasions I was able to identify it and the effects were very different from ayahuasca, and its effects are very interesting because it brings out the ego, the neurosis, the most strident pain, and thanks to harmaline we experienced a collective session of bringing out our most explicit neurosis, with a painful self-confrontation. It was not a session where you go to heaven, but rather a hell, or at least a purgatory.

We can say that in Claudio’s relationship with ayahuasca there is a stage prior to the publication of the book and another much later, from the 1980s onwards, when Claudio came into contact with the Santo Daime.

The truth is that his first contact with ayahuasca is through science, with Schultes, or also with Leo Zeff, who was known as the “chief of psychedelics” in California in the 1960s, and from there he came into contact with the Kofan Indians of Colombia, and ends up being recognised as a taita by the Kofan and other traditions, and even has a curious exchange of ayahuasca for LSD blotters with interesting results, which he describes in ‘Ayahuasca, la enredadera del río celestial’. It was then that he came into contact with the Santo Daime and integrated it into his work. It is curious that today there are daimistas in Brazil who form their own church in order to be able to work freely with Claudio Naranjo’s psycho-spiritual proposal. Concretely, this proposal leads to a very powerful integration the next day through a wide range of integration tools, developed in the SAT programme.

What church is this?

It’s called Centro Som de Despertar and it’s in Brasilia. In Brazil, belonging to a church gives you legal protection. Claudio had taken precautions, he had had a very difficult time during the sixties and seventies because of the aforementioned war on drugs, while in Brazil he could work freely and do his work legally.

What was an ayahuyasca intake with Claudio like, how is it similar to and different from, for example, a Santo Daime “trabalho”?

The Santo Daime takings are very structured, in which the collective experience is of great importance. In Claudio’s case there were several phases: one was collective, gathered around him, where we worked with classical music and also with Tibetan chants, you have to remember that Claudio was a scholar of Tibetan Buddhism, as he was an integrator between Western psychology and Eastern philosophies, and sometimes there was also some music from ayahuasca and Sufi religions. He took people to very intense territories through the music, and from there there were concrete meditation instructions, which are already part of the “therapeutic secret” of Claudio’s work, followed by a space for everyone to individually elaborate the experience, and finally there was a part of collective celebration… whoever could stand, which was not everyone. On the following days, a large space was dedicated to the integration of the experience.

Who came to these ceremonies?

I am talking about sessions for people who had taken many times with him, because Claudio only invited people who had previously worked with him or, at least, had a deep therapeutic work behind them: Buddhist meditations, dzogchen, Sufism, Vipassana… all of this, together with Claudio’s inspiration, produced moments of paradise and also moments of hell, but very well used. The result was a profound and extremely transformative work, also in people that other therapists did not dare to accept in their work with psychedelics for purely precautionary reasons. It is curious that in more than fifty years of therapeutic practice no one had ever suffered a psychotic break, and I know this because I asked him directly. In the many years I was with him I never saw a psychotic break either, and we are talking about thousands of people, which means that it would have been almost “forced” to happen at some point.

However, it is still taboo to open the door of ayahuasca to people with bipolar syndrome or schizophrenia.

I think he knew enough to take risks and, at the same time, I have never seen such a careful environment as in the sessions organised by Claudio Naranjo. A discreet environment, with the best psychotherapists at his disposal, and with his experience we were achieving things that, I hope, will be seen in the years to come.

It is not very common to use classical music in ayahuasca ceremonies, but Claudio played Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, an experience that must have been overwhelming.

There are several therapeutic tools developed by Claudio, some of which are not yet known because he took great care to protect his work. The Enneagram was shot down by thousands of sugar-coated “Enneagrammers”, as I call them, in the United States in a rather embarrassing way. But of course there are two essential tools: one is interpersonal meditation, which Osho took up, popularised and publicly thanked Claudius very much for. The second is the use of classical music in the psychedelic environment. Claudio Naranjo used to say that the great composers were the ‘tulkus’ of our culture. He said this about Beethoven, Brahms, Mozart… Bach, of course, not Wagner. If we look at Beethoven’s life we see the story of a hero’s journey: the story of a man who wants to “grab God by the throat and wring his neck”, in his own words in his heroic stage, but who gradually, through deafness and suffering, realises that life is something else and finally, when he reaches maturity, bears its best fruits. And it is not the war against God but that immense ode to Humanity that is the Ninth Symphony. Listen to it under the effects of ayahuasca and feel its “organismic” effect, to use again this term from Gestalt. The same could be said of Brahms, whose Symphony No. 1 is perhaps the most sublime work ever composed. It makes sense that all this spiritual heritage of the West should be integrated with ayahuasca, and not, as it seems, in a museum urn with camphor pellets. Claudius understood this and applied it.

Collage by Lori Mena, via Kahpi.net.

What else can you tell us about the partnership you had with Shulgin, the great chemist?

It was a rather peculiar bond. In the mid-1960s a bond began between Shulgin, Sargent and Claudio. Shulgin has gone down in history as the great designer of what is known today as “designer drugs”. In reality, during this, Shulgin’s most creative stage, what we really have is a partnership between a chemist and a psychiatrist specialising in psychopharmacology, Claudio Naranjo. They are such brutes that when they design a substance they test it on their own body to regulate the dose, it is surprising that they haven’t burnt their brains in the experiments, because they have taken hundreds and hundreds of psychedelics, from which they not only come out alive but in better health. After regulating the dose, Claudio gives it to a group of volunteers to study the specific therapeutic effects of the substance, from MDMA to 2CB. Little by little, they come up with more than 200 substances, an incredible work about which we know little, apart from the numerous scientific articles they write. The problem is that they end badly, they break up, and Shulgin completely denies Claudio and even in his book ‘Tihkal’ leaves him at the height of the bitumen; assuring that Naranjo did not listen to Schultes, when the truth is that he had a long and profitable professional and admiring relationship with him. I think they competed, that Claudio lost out and that Shulgin was not honest in not acknowledging Claudio’s important work in synthesising and analysing the therapeutic effects of so many psychedelic substances.

I see quite a lot of ingratitude here on Shulgin’s part.

Claudio was a very shy man, who didn’t claim himself and especially in this stage of the seventies, which he went through in a very discreet way, after an experience with Óscar Ichazo in the desert, where he had a kind of enlightenment. After that he makes quite a lot of noise in California and then turns off the light, leaves the room and Claudio Naranjo is not mentioned again until the mid-1980s when he arrives in Spain. This phase, which is a phase of dark night of the soul, he feels very abandoned and unrecognised by the psychedelic community in California and by the transpersonal community, of which he is one of the pioneers. It is only recently that the figure of Claudio Naranjo has been recovered in California, who was considered a legend of the sixties, something like Castaneda, who was his great friend, by the way.

Maybe he would have been less shy and more messianic, he would have founded his own church.

I think it would have been a great idea and, in fact, I claim that Gestalt therapy should be constituted as a big church since those who claim that psychology is a science do not respect what they call “alternative therapies”, although Gestalt is not an alternative therapy, it is a therapy. However, in the academic and cognitive-behavioural world there is a respect for religion, they are like the two saturnal brothers: science and religion, the two wild beasts that organise the game of our culture. So I think it’s not a bad idea that Gestalt ends up becoming a church, so we save ourselves a lot of trouble in front of the corporate gaze of the professional associations and whoever wants to can get a religious card, and we’ll go to church to sing, we’ll go naked and have orgies under the effects of ayahuasca and everything will be bread and circuses… I’m being ironic.

Not to mention the legal protection that nowadays only the ayahuasca churches have to import ayahuasca and give it to their faithful as a sacrament.

It is laughable. We hope that this panorama will change, and it is going to change very soon because the legalisation of MDMA and psilocybin is very advanced in the United States and, if all this happens by the middle of this decade, this psycho-therapeutic use of psychedelics will end up reaching Europe and, little by little, we can stop living in this kind of limbo in which one has to declare oneself faithful in order to have a consumption that is already responsible in itself. There has to be an extra responsibility for something that has been so unfairly criticised by politicians and the media to have the place in society and in science that psychedelics deserve. This will happen, no doubt about it, and now is the time when it is finally going to happen.