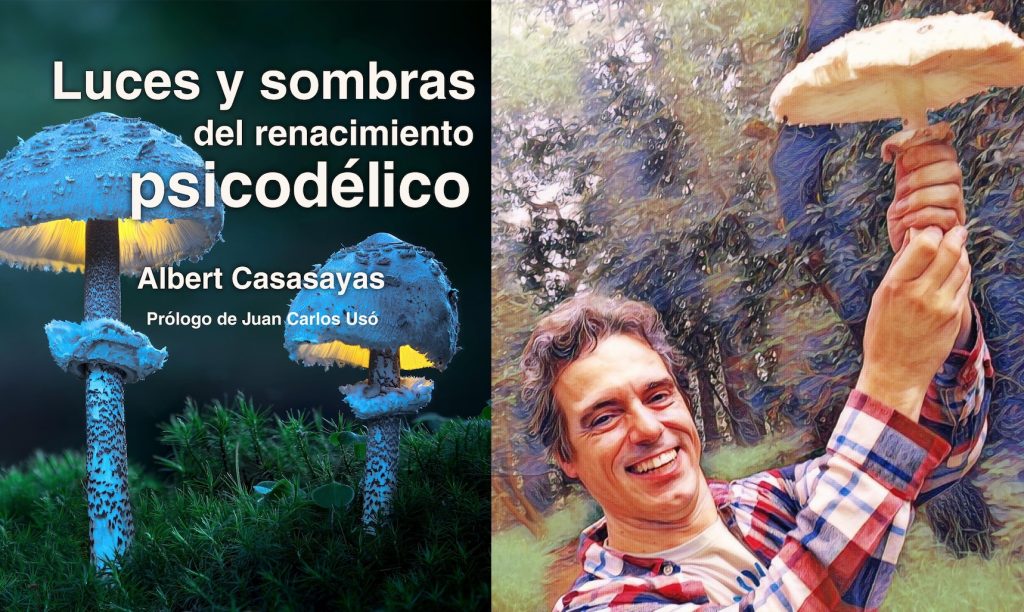

The psychedelic renaissance is the talk of the town, currently enjoyed on therapy couches and meditation mats of a privileged few. Albert Casasayas tackles issues such as like inequality in access to psychedelics and the so-called “psychedelic exceptionalism” in his new book ‘Luces y sombras del renacimiento psicodélico’, which has been published by Revista Ulises and available for free on the Universo Ulises website.

Albert Casasayas teaches Spanish and Latin American Studies at Santa Clara University in California. He admits he’s a newcomer to psychedelia or, according to Juan Carlos Usó, who wrote the book’s prologue, a “neo-convert.” This fresh look at psychedelics is one of the book’s greatest strengths. The book is not intended to be academic, but rather a “middle-ground” perspective, distinct from those deeply involved in the psychedelic community but also beyond the “very biased mainstream media with its anti-drug discourse.”

Speaking via Zoom from California, Albert is preparing for the imminent academic year while continuing to delve into the complex, fascinating, and often paradoxical world of visionary drugs.

“The anti-drug industry moves millions in the United States”

‘Luces y sombras’ delivers a fierce critique against the war on drugs, adding a new voice to those who have long denounced the disastrous experiment launched by Richard Nixon five decades ago: “The neo-colonialist atrocity that is the war on drugs had devastating effects throughout Latin America.”

While it’s undeniable that drug cartels move large amounts of money, Casasayas asserts that “the anti-drug industry involves a judicial, prison, and medical machine that moves millions in the United States. No one questions that major media outlets writing against drugs do so from a biased perspective. Big media outlets are often owned by conglomerates with economic interests in sectors such as health, security, and prisons”

Spiritual Growth vs. Degenerate Addicts: The “Psychedelic Exception”

The book doesn’t skirt around a noteworthy phenomenon: as their use broadens and becomes destigmatized, psychedelics are transitioning from being categorized as “drugs” to “medicine”. This creates a sort of psychedelic elite, which, by culture and social status, aims to differentiate itself from users of other psychoactive substances perceived as more addictive or damaging. It’s the so-called “psychedelic exception” that Carl Hart discusses in his book ‘Drug Use for Grown-Ups,’ which Casasayas enthusiastically recommends.

“Some things, and this is not limited to the world of psychoactives, are perceived negatively depending on who does it: consuming psychoactives is portrayed as an example of vice and social degradation when done by the lower classes, but when the middle and upper classes consume psychedelics, then it’s seen as seeking healing from traumas and as a form of spiritual expansion.”

“Suddenly, figures in Silicon Valley start using microdosing for enhancing productivity for ‘creative expansion’, while New Age communities talk about ‘holistic healing’ with plant medicines. These are somewhat exclusive consumption modalities, while less privileged communities, using other drugs continue to be violently suppressed by police action. We cannot ignore the social dimension in the use of psychoactives,” explains Casasayas, who argues in his book that liberation should occur with all kinds of psychoactives, or it won’t be liberation in the true sense of the word.

“There is no pill that can cure the toxic structure of alienating capitalism”

In this vein, “research focused on veterans with PTSD (MAPS) has neglected less privileged and larger groups, like addicts, because they have a worse social reputation,” writes Casasayas on page 89 of ‘Luces y sombras.’

However, another shadow in the psychedelic renaissance is that we can’t pretend that a psilocybin pill can cure the alienation created by the capitalist system:

“If we live in a toxic structure like alienating capitalism, no pill can cure this. We need to love and be loved, connect and share with our environment in meaningful ways, with hugs and laughter. Good mood and good love, I say. A that a system attempting to colonize and monetize even the most intimate aspects of human experience (can provide, from dating apps to the deepest content of our psyche) can’t provide any of this.”

The Lights and Shadows of Decriminalize Nature

Decriminalize Nature is an undeniable protagonist in discussions about the psychedelic renaissance in the U.S. This network community organizations has achieved significant success in decriminalizing psychoactive plants in several U.S. cities (Oakland, Seattle, Detroit, Denver…) but has also clashed with the Native American Church over the consumption of peyote, considered sacred by the country’s original inhabitants:

“I respect Decriminalize Nature for the undeniable success they’ve had in decriminalizing master plants in several U.S. cities. On the other hand, last year they released a manifesto saying ‘We are all natives to mother earth, we are all indigenous.’ This sounds lovely, but from a social perspective, those who have suffered centuries of discrimination, persecution, and economic, judicial, political, and cultural violence are those labelled indigenous. It’s nice to say we are all indigenous, but this disregards the historical reality of this and many other countries.”

“On the other hand,” the writer points out, “in Real de Catorce (San Luis Potosí, Mexico), there is a significant loss of wild peyote plants, and anthropologists on the ground accuse the Native American Church of being the main drivers of this illegal extraction.“

“This is a very thorny issue. The NAC is a relatively recent syncretic religion, but some of its practices have ancient roots. Its members suffered discrimination, legal persecution, and cultural disdain from a hegemonic white majority until just a few decades ago. On the one hand, the idea that belonging to a religious creed assures you special rights over a plant is hard to defend in a theoretically secular constitutional environment. On the other hand, it must be truly irritating that something sacred to you, for which your community has suffered abuses, suddenly becomes a commodity when the white majority discovers its virtues. It’s even worse when it concerns an endangered plant.”

“However, I notice in some arguments from the NAC and allied organizations a confusion between religious belief and ethnicity. There are also some positions I fail to understand: the opposition to personal cultivation of the peyote cactus (lophophora williamsii) and sometimesalso the opposition to the decriminalization of huachuma or San Pedro cactus (echinopsis pachanoi). As far as I can understand, these actions would help reduce the pressure on wild peyote.”

‘Luces y sombras del renacimiento psicodélico’, can be found on Universo Ulises.