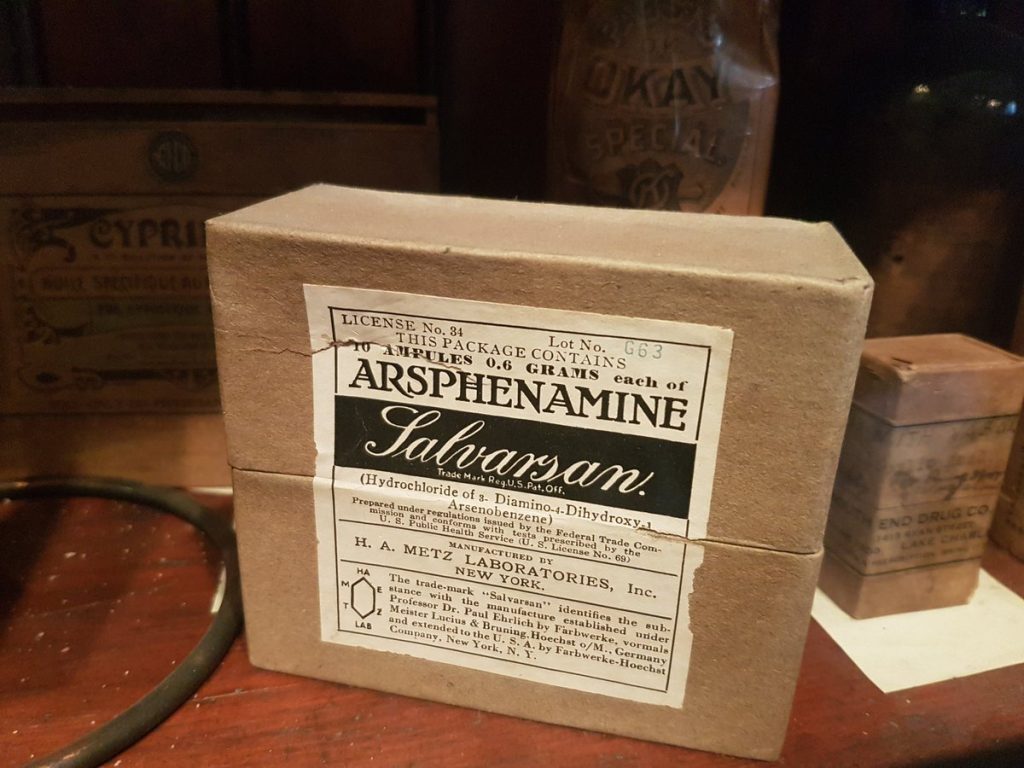

In 1910, the German bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich made a groundbreaking discovery and patented arsphenamine, a chemical compound derived from arsenic that proved effective against syphilis and was marketed for two decades under the trade name ‘Salvarsan’.

Ehrlich, who had already been awarded a Nobel Prize for his vaccine research, had a profound impact on 20th-century pharmacology with his concept of the “magic bullet”:a pharmacological compound that specifically targets a particular pathogen without harming the host’s body.

‘Salvarsan’ was the first successful drug based on the “magic bullet” hypothesis and saved millions of lives in Europe until the introduction of penicillin, discovered by Alexander Fleming two decades later. Penicillin proved to be more effective than ‘Salvarsan’ for treating syphilis and other infectious diseases. However, the echo of Ehrlich’s discovery and the “magic bullet” concept continues to resonate, albeit with diminishing influence.

“For some time now, selective drugs specifically designed to target a single element in our body have proven to be ineffective,” explains pharmacologist Genís Oña from the ICEERS Foundation in a conversation with Plantaforma. Oña, along with the ICEERS research team led by José Carlos Bouso, is investigating and promoting the “new paradigm” of pharmacology: polypharmacology. This emerging field integrates and surpasses the traditional approach, while providing a framework to explain the effectiveness of herbal remedies and plant compounds. In Oña’s words:

“They began researching products that were less selective but had an impact on a complex system of genes, cells, and tissues associated with a complex disease. Through these studies, they realized that the classical pharmacological paradigm did not work in explaining these effects because it forces you to break everything down and reduce complex effects to the simplest effects of specific molecules. When studying a complex product composed of multiple plants, with hundreds or thousands of molecules affecting thousands of targets in the body, the classical paradigm falls short.“

“From there, and with the emergence of new techniques such as transcriptomics and metabolomics, it became possible to study these complex phenomena and create comprehensive maps of these complex products. Simultaneously, observations revealed that these products are often more effective and safer than complex drugs. This is leading to a revolution in pharmacology, and it is expected to gain more prominence in the coming years. Not only in pharmacology but also in various disciplines, there is a growing tendency to embrace the complexity of phenomena rather than the reductionism that has been predominant for over a century, stemming from French positivism. There is a shift towards embrancing complexity”.

To date, Genís Oña and José Carlos Bouso have published three articles on polypharmacology. The first article specifically explores the potential of psychoactive substances such as cannabis or ayahuasca in treating neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s. It strongly advocates for the use of whole plant compounds instead of isolating their active principles, aligning with the direction of the so-called ‘psychedelic renaissance’ and building upon the reductionist approach of Ehrlich’s paradigm.

Polypharmacology, according to Oña, “reminds us that consuming the entire herbal product with all its active components—something that has been practiced for centuries—might be the key to achieving real therapeutic effects. Instead of administering psilocybin pills, for example, it may be more beneficial to use the whole mushroom, as has been done traditionally”.

Ayahuasca in the light of polypharmacology

Ayahuasca, when examined through the lens of polypharmacology, remains a subject of limited scientific knowledge. Only its active ingredient, DMT, and the beta-carbolines that activate it—harmine, harmaline, and tetrahydroharmine—have been studied. However, little is known about the approximately 2,300 to 2,400 compounds present in ayahuasca, many of which possess neuroprotective properties. These molecules aid the plant(s) in their survival, protecting them from insects or seeking sunlight, but they can also have a profound impact on human beings:

“There is a blend of compounds that always work together, not subtracting from each other. If they contribute to a therapeutic effect, even if it is not specific to the individual’s disease, it can bring benefits,” summarizes Oña. The implications of this line of research are vast, not only for understanding the concept of plant intelligence advocated by botanist Stefano Mancuso but also for our own biology and the co-evolution of the species involved.

“Over the millennia, ayahuasca has refined its biochemical profile to better adapt to its environment. Through the friction and coexistence in the forest and its ecosystems, a specific phytochemical profile has emerged, which we can leverage. It is fascinating, and if a new paradigm helps us better comprehend such a complex and diverse plant, we should fully embrace it.”

“Over the millennia, ayahuasca has refined its biochemical profile to better adapt to its environment. Through this friction and this coexistence in the forest and its ecosystems, a specific phytochemical profile has been emerged, which we can leverage. It’s fascinating, and if a new paradigm helps us to better understand such a complex and diverse plant, we should fully embrace it.”

Genís Oña, pharmacologist and science coordinator at ICEERS.

The complex interaction of thousands of molecules with millions of cells and hundreds of targets cannot be replicated with a just a few active ingredients or by substituting them with so-called “ayahuasca analogues”, as they were coined by renowned ethnobotanist Jonathan Ott in his 1994 book of the same name. While these analogues may produce psychoactive effects similar to ayahuasca, they do not possess the same profound healing effects as the Amazonian brew.

In the words of Genís Oña, “that would be another type of reductionism: solely focusing on the psychological effect of the plant on the individual. While these psychoactive effects may indeed have benefits, the plants used to create ‘farmahuasca’ or ‘anahuasca’ are not as extensively studied as Banisteriopsis and Psychotria. Consequently, there may be compounds, such as Peganum harmala, which are known to have abortifacient properties. It is possible that for certain diseases, the traditional recipe is more effective, while for others, an alternative recipe may work better.”

Pharmacological reductionism, or psychonautical reductionism, also influences fields such as the legislation, which often aims to persecute and punish specific molecules present in certain plants—such as DMT in ayahuasca; THC in cannabis or cocaine in coca leaves. This reductionist perspective stems from the notorious ‘War on Drugs.’

“Instead of focusing solely on the active principles, ideal legislation should not only avoid pharmacological reductionism but also cultural reductionism. In other words, we should not reduce the coca leaf solely to cocaine since the coca leaf has incredible licit uses—textiles, food, etc.—that are overlooked when everything is reduced to its active ingredients, disregarding the cultural applications of the entire plant,” concludes Genís.

*As evidenced by the more than 8,000 references that Spanish pharmacies currently handle, all of them inspired by the principle of the ‘magic bullet’.

Links:

–’Therapeutic Potential of Natural Psychoactive Drugs for Central Nervous System Disorders: A Perspective from Polypharmacology’, Current Medical Chemistry, 12 de diciembre de 2019.

–‘Whole Natural Products in Psychedelic Research and Therapy’, ICEERS Foundation, 2019.

–’On the origins of drug polypharmacology’, Xavier Jalencas y Jordi Mestres, Journal MedChemCom, 2013.