The botanical classification only includes two species of ayahuasca, the famous Banisteriopsis caapi and the lesser known Banisteriopsis inebrians, a gnarled vine that is also used, less frequently, to make the Amazonian medicinal concoction. However, traditional indigenous peoples contemplate a wide range of ayahuasca vines, not only in terms of colour and morphology, but also in terms of their effects.

The taxonomy of Amazonian plants by indigenous and mestizo healers and shamans is no less precise or “scientific” than that offered by botany. In fact, more and more researchers are trying to build bridges between traditional knowledge and the western Cartesian vision, two complementary approaches with the same objective: the attainment of knowledge.

This is the case of the remarkable Canadian anthropologist and populariser Jeremy Narby, precocious author of the book ‘The Cosmic Serpent’ (republished in Spain in 2020 by Errata Naturae), who has published ‘Plant Teachers: Ayahuasca, Tobacco, and the Pursuit of Knowledge’, a booklet (just 136 pages without waste) that summarises his conversations with Rafael Chanchari Pizuri, a plant doctor and political activist of the Shawi ethnic group, based in Iquitos, capital of the Peruvian Amazon.

Chanchari and Narby establish a fruitful intercultural dialogue around two sacred plants, tobacco and ayahuasca. Anthropologist Narby, who has been listening to and learning from the indigenous people of the forest for more than thirty years, reconciles indigenous and scientific knowledge. For example, the allergy of any scientist to the “spirits” that often inhabit the indigenous animist worldview is well known. However, Narby dissects Shawi terminology to conclude that when they refer to “spirits” they are referring to “the invisible”, so the “spirit” of ayahuasca or tobacco is more akin to molecules and active ingredients than to the “soul” we are used to hearing with Cartesian scepticism.

The varieties of ayahuasca

The first two chapters/lectures of ‘Plant Teachers’ are dedicated to tobacco, the master plant par excellence of the Amazon and the whole American continent. It is a plant that is very well studied by science, but it also carries a strong stigma, being associated with industrial tobacco and its millions of dead and sick, motivated by the prostitution of this sacred plant.

As far as ayahuasca is concerned, Rafael Chanchari distinguishes between “many varieties of ayahuasca –cielo, trueno, mariri, rayo– with different characteristics. You can distinguish them by their colour; generally speaking, there is black ayahuasca and yellow ayahuasca, but when you go into more detail, there is a whole range. Yellow ayahuasca is known as “heaven” and is used for medicine and for vision. That’s the one I drink, and in my garden I only plant ‘heaven’, not the other varieties, which teach you evil and witchcraft; I don’t drink those, although other people do”.

(…) “Sky ayahuasca is yellow when you scratch the vine, while black ayahuasca has a dark colour. There are several types of black ayahuasca: trueno and mariri, and both have small knots on their main trunks. It is easy to distinguish one from the other by its colour and shape”.

The distinction between these varieties of the vine is not trivial. When asked by his interlocutor, Jeremy Narby, whether it is dangerous for a foreigner to drink ayahuasca without knowing the difference, Chanchari replies:

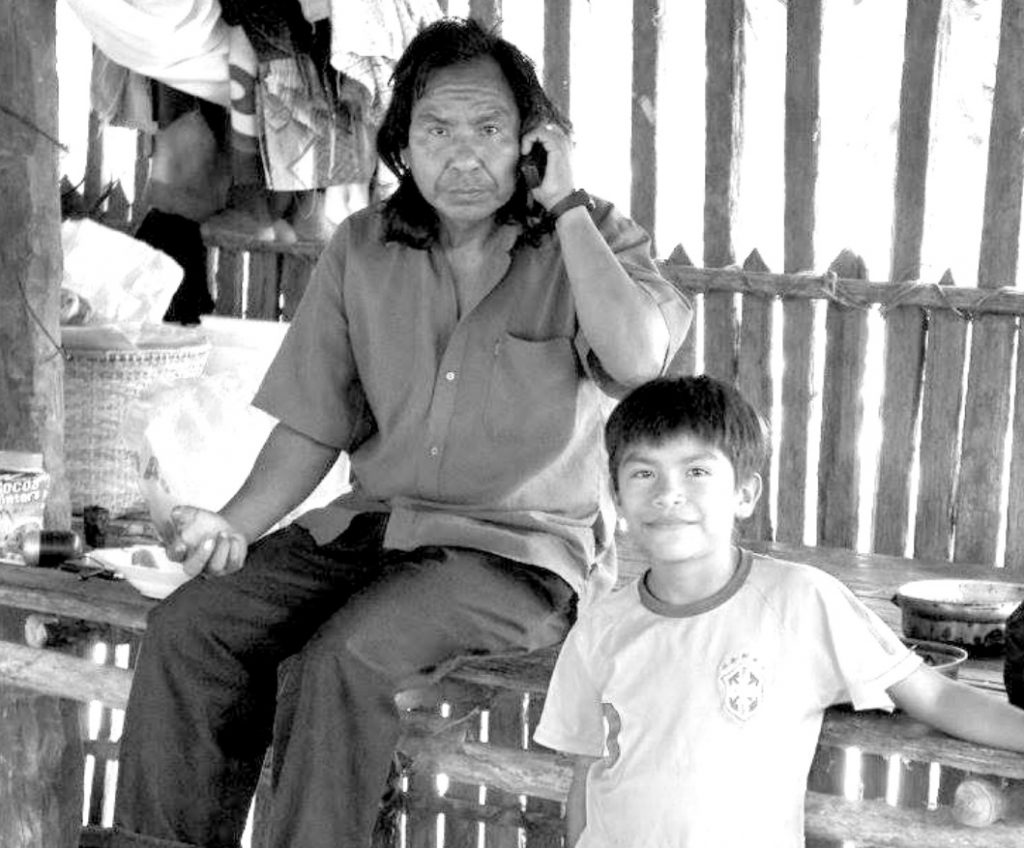

Photo: ‘The two halves of Rafael Chanchari Pizuri’.

“Yes, it is dangerous; it is risky. I’ll tell you my experience: I started taking ayahuasca alone, because my grandfather was an ayahuasquero, as was my uncle. Later I met my teacher, Fermín Murayari, he was a doctor. I told him “Master, I want to learn”, and he replied, “I will teach you, but it won’t be me who does it. It will be the spirit of ayahuasca that will study what kind of person you are and what you are capable of learning. Then you will learn.

Master Fermín and I drank together about fifteen times. One night he scolded me for drinking ayahuasca by myself: “Why are you learning witchcraft? That is not good because you are going to kill children, and their parents will suffer. You will kill women, and their husbands will suffer. You will kill husbands, and their wives will also suffer. Eventually, a bullet will kill you (…) I will clean you. And we can go on drinking.

The next few days, every time I drank ayahuasca, I sweated like never before. Usually, I didn’t sweat, but during those days, I sweated a lot, and that’s how it cleansed me. As I did this, I passed many tests; ayahuasca is used to test the people who take it. I felt fear. I could see the whole cosmic world, it was full of suffering and I found it quite discouraging. I was about to tell my master that I wanted to stop drinking ayahuasca. However, that last night I saw no more suffering. Everything became transparent, clear and calm. The spirit said to me “Now put this into practice. Contact the people you would like to communicate with”.

(…)

Chanchari believes that, to avoid any danger, visitors “should ask what kind of ayahuasca they are going to drink. Doctors cannot lie. That’s one of the things ayahuasca tells you: you must never cheat. You have to be honest, that means you can’t lie to people. If you serve black ayahuasca, you have to tell people that it is black ayahuasca, and if it is yellow, it is sky ayahuasca. Then, foreigners can decide whether to take ayahuasca or not” (…).

“Ayahuasca has multiple mothers and souls, which can be transformed into different natural beings. If it is yellow or sky ayahuasca, it is associated with the yellow boa, and if it is black ayahuasca, with the black boa. Sky ayahuasca has its own icaro. It goes like this: ‘u ru ru ri, u ru ru ir’, and when you chant this, the boa comes, shining and full of lights. That is the ‘uru‘, which means ‘to shine'”.

Narby, with Asháninka teacher Juan Flores (left).

Another botanical taxonomy is possible

The ayahuasca vine was first identified and classified by the eminent botanist Richard Spruce, who had the opportunity to taste the Amazonian concoction as early as 1852 in the Brazilian town of Urubú-coará. It was Sprue who classified Banisteriopsis caapi within the genus Banisteriopsis, in the order Malpighiales.

The first phytochemical study of Banisteriopsis caapi took place at the beginning of the 20th century, when in 1905 the Colombian pharmacist Rafael Zerda Bayón isolated an alkaloid from a sample of yagé, which he called “telepathine” because of the supposedly telepathic properties of the drink. The last scientific classification of the genus Banisteriopsis was made by the American researcher Bronwen E. Gates, as far back as 1982.

Although, as we mentioned at the beginning, there are two species of ayahuasca liana within the botanical classification, some scholars propose to extend this classification to include the different varieties that distinguish the native peoples, both in terms of their physiology and their effects. This is the case of Brazilian researcher Regina Celia de Oliveira, who in an article published in Chacruna in 2018 called for an “urgent revision of the botanical classification of the ayahuasca vine”. Oliveira and the other signatories of the article (Christopher Wagg, Bian Labate and Julian Sonsin Oliveira) try, like Narby, to build bridges between indigenous and scientific knowledge, although, they acknowledge, “most indigenous knowledge has not been systematically recorded, or appears in remote and inaccessible ethnographies, and these findings and notes have not been compared and contrasted with current botanical knowledge”.

Did you like the article? Become a member of Plantaforma so that we can continue writing many more.